View of Lothagam North Pillar Kenya, built by eastern Africa's earliest herders around 5000 years ago, researchers say. Megaliths, stone circles, and cairns can be seen behind the 30m platform mound.

Updated 1053 GMT (1853 HKT) August 23, 2018

Lagos, Nigeria (CNN)Kenya's arid, gullied Lothagam Valley is a throwback to a very distant past. Now, the region is the site of a discovery that has the potential to change how the world views ancient societies and the way they operated.

A team of researchers from Stony Brook University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History have discovered a massive, elaborate cemetery in the region that is the largest and oldest in Eastern Africa. Here, temperatures can rise to 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit), and the vast, rocky landscape can look like a desert planet from the "Star Trek" movies -- or Mars.

"This discovery challenges earlier ideas about monumentality," said Elizabeth Sawchuk of the Department of Anthropology, Social & Behavioral Sciences at Stony Brook University in New York.

For decades, Lothagam's well-preserved grandeur has fascinated archaeologists. The researchers wanted to study a large community of animal herders thought to have built the Lothagam North Pillar site, a communal cemetery, about 5,000 years ago.

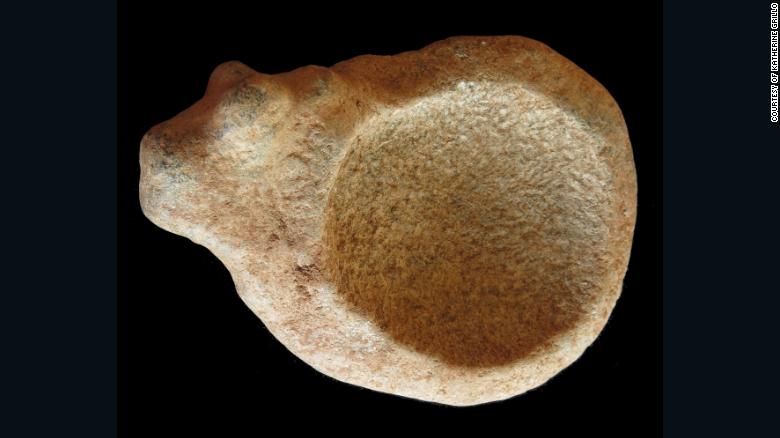

The herders built a platform approximately 30 meters in diameter, with a deep cavity where about 580 men, women and children were buried side by side, each wearing nearly the same amount of ornaments, and no sign of special treatment.

Local tribes have revered the sites for years, according to Sawchuk.

"They regard the pillars as dancers turned to stone after they laughed at a god who visited them in disguise wearing strange clothes," Sawchuk said. "The Turkana do not consider themselves descendants of these people, but they watch over the sites and make sure that they are protected."

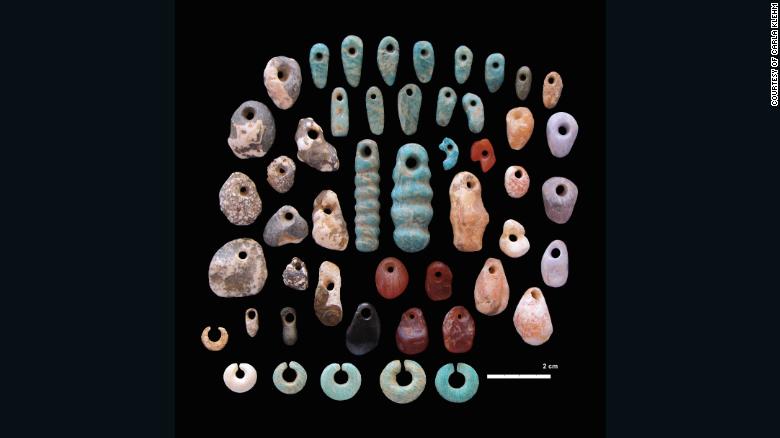

The ornaments uncovered at the site, elaborate and resplendent pendants and earrings made of ostrich eggshells and stone, reflect the herders' expertise.

"The jewelry would have had great value, as each bead would have taken many hours of skilled labor to carefully grind down and shape," Sawchuk said.

Beyond revealing the level of their skill, they also indicate how the society was structured.

"They may have been a way for people to show who they were, the group they belonged to, and the strength of their social networks," Sawchuk said.

The findings suggest that the pastoralists, who led a mobile lifestyle, had a community in which everyone was equal -- an egalitarian society.

"Until recently, archaeologists thought that emerging elites instigated monumental constructions to simultaneously bolster their own authority and serve as symbols of social unity," said Elisabeth Hildebrand, associate professor of anthropology at Stony Brook University.

Simple society, complex achievement

Scientists have long viewed ancient monuments as "indicators of complex societies with differentiated social classes," the archaeologists said in a statement.

A familiar example is the Pyramids of Giza, built by the ancient Egyptians under the direction of their powerful pharaohs.

"Ancient monuments have thus previously been regarded as reliable indicators of complex societies with differentiated social classes," the archaeologists said.

However, the Lothagam North Pillar Site defeats that theory.

"These motives may well have been the case among sedentary farmers, but the finds at Lothagam North Pillar Site show that some instances of monumentality developed for other reasons that did not relate to elites," Hildebrand said.

Instead, this site showcases unity.

"By constructing the mortuary cavity, people created a shared space where community members could be placed all together, without any sign of certain individuals being given primacy," Hildebrand said.

"The close positioning and irregular orientation of burials within the cavity suggests that again, no individual was being ranked over other people. All of this shows us that the building and use of Lothagam North were not done to serve some emerging elite class, but rather to create unity across an entire community."

The discovery gives credence to similar large, monumental structures built by groups thought to be egalitarian in Africa and other continents.

After Lothagam's herders buried their dead, they covered the cavity with stones and placed large stone pillars.

Other stone monuments were laid nearby, they said.

"The monuments may have served as a place for people to congregate, renew social ties, and reinforce community identity," said Anneke Janzen of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

Lothagam's rich past

The Lothagam site is close to Lake Turkana, a vast body of water that sustained groups of hunter-gatherers and fishers living around the lake, and eventually the mobile pastoralists, according to Hildebrand.

"Today, Lake Turkana gets about 90% of its water from the SW Ethiopian highlands via the Omo River, and the remaining 10% from the western Kenyan highlands via the Turkwel and Kerio Rivers. During times past, rainfall in all these areas fluctuated, and Lake Turkana expanded and contracted as weather systems changed," Hildebrand said.

The conditions would worsen and improve over the years, as herding was introduced to the area.

Today, Lothagam is littered with stone tools, harpoon tips, pottery, and animal remains that offer a glimpse into prehistoric life in Africa.

Hildebrand said the discovery of the cemetery should make Kenyans, and Africans, proud of the "deep cultural traditions" among one of its oldest civilizations.

"In a certain sense, these early herders formed the first civilization of eastern Africa with elaborate individual and community practices. In today's time of climate change and economic instability, we can all take a very important lesson from eastern Africa's first herders: Facing an equally challenging situation, they responded by coming together and strengthening their community," Hildebrand said.

No comments:

Post a Comment