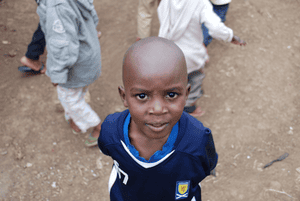

Kibera's slums assault the senses

like a barbeque in a hot toilet. Raw waste carves gullies along the ragged ribbons

of bare earth that serve as side streets and alleys, where children crawl and

play in dirt you wouldn't step in unless you had to; for all my cringing,

nobody seemed to mind much. Forests of twisted aerials sprout from the rooves

of shacks raised up from the mud and topped with sheets of metal. The main

streets are full of the hustle and bustle of the ultimate free market, the sort

of anarchic community libertarians beg for, but would beg to be rescued from.

AirTel signs and M-PESA logos compete with butchers and charcoal-sellers,

bombarding the senses with a barrage of colour that still can't quite match

that smell.

From time to

time celebrities are deposited in the slums by shiny new trucks, where they cry

at children to appease the gods of television and self-promotion. Like the

increasing numbers of 'slum tourists', they flaunt their privileged ignorance,

inspiring bemusement - sometimes contempt - in locals who take pride in the

thriving, entrepreneurial community they carved out of barren earth. Ground

long since disowned by Nairobi, a city that surrounds Kibera the way a brown

paper bag conceals a dirty magazine.

My mind

wandered, and I imagined how I would react if I were in her shoes, fielding the

same inane questions about my own life. "So Martin, what's it like being so

sick and poor?" "Well Martin, it's pretty fucking

miserable." "What can people do to help,

Martin?" "I need medicine, Martin, and some

money." "Is there any point to this interview,

Martin, or is this just poverty porn?" "Do

you have a question, Martin?"

None of this conversation was 'real'; it took place through translators provided by our hosts, a local community project claiming to represent Kibera's youth, and yet comprised almost entirely of people in their 20s or older. Attractive, bright, and enthusiastic, they had an uncanny talent for taking a few mumbled words of Swahili and turning them into the neatly-packaged on-message anecdotes beloved by the sort of cynical vultures that film the 'guilt segments' for telethons.

If you're not careful in these situations you can find yourself interviewing the translator instead of the subject; but the heat and the smell of open sewers and the close air and the dust and the boredom and the warm sweat running between your shoulder-blades wear down your concentration. As the minutes wore on our AIDS victim faded into the background, replaced by the impression of a helpful NGO worker, a smiling avatar spinning stories to the tunes of Coldplay. It was only later, replaying the scene in my head that I began to wonder; who exactly were we listening to?

And as I

looked more closely at the slum that day, other niggling thoughts buried deep

in my subconscious begin to trace their way to the surface. Why were the

members of this 'youth' group so old? Why was everyone who spoke to us being

paid in cash or food? Why hadn't the sick child we saw earlier been taken to

the free MSF clinic nearby? Who were the gangs of young men standing sentinel

by local community facilities? Were we visiting a legitimate aid organization,

or a lucrative local industry? How many people lived in Kibera anyway?

That morning, back in the

post-colonial surroundings of our overpriced hotel, I had watched an array of

speakers try and fail to give a consistent answer to that one simple question:

how many people live in Kibera? Their figures varied but were all measured in

millions, one enthusiastic chap claiming as many as five – something of a

stretch given that Nairobi's entire population is only

around three million.

A quick

search on Google finds page after page of estimates in or around the same

ball-park. The White

Housereckon it's "just about 1.5 million",

while the BBC claim 700,000. Jambo

Volunteers say "more

than one million."The rather sickly-sounding Global

Angels reckon "around

1 million." TheKibera Tours website

describes "a population estimated at one

million."The Kibera Law Centre gives "almost

1 million." Shining

Hope for Communities reckon

that Kibera"houses 1.5

million people." The Kibera Foundation talk about "a

population of almost a million people," as do Kibera UK and about a hundred other sites you

can find through your friendly neighbourhood search engine.

A week

later, Harper's Jeff Sharlet and I returned for our

own trip; a three-mile hike across the slums with a local fixer we knew. Our

mission: to see if we could find something that was interesting, or real, or

ideally both. Walking from thePamoja FM studio in the middle-class Ayany

district at the west of Kibera, to Lindi in the east, we passed through several

of Kibera's thirteen villages, and confirmed what I already knew from previous

visits to Kenya - the idea that Kibera holds a million people is completely and

utterly absurd.

That much is obvious if you just

visit the place and spend a few days wandering around it; actually looking at it. Kibera consists of around two

square miles of densely-clustered, single story shacks. For the White House's

estimate to be accurate, Kibera's cluttered streets and labyrinthine alleyways

would have to support a population density thirty times higher than the

towering skyscrapers of New York. All the crow bars and grease in the world

could not fit that many people into that small a space.

The mythical

million comes from estimates built upon estimates that have spread over the

years like Chinese whispers through the NGO community and, later, the internet.

Paul Currion laid out how this works two years ago, in his essay "Lies,

damned lies and you know the rest":

In the absence of actual data (such as an

official census), NGO staff make a back-of-envelope estimate in order to plan

their projects; a postgraduate visiting the NGO staff tweaks that estimate for

his thesis research; a journalist interviews the researcher and includes the

estimate in a newspaper article; a UN officer reads the article and copies the

estimate into her report; a television station picks up the report and the

estimate becomes the headline; NGO staff see the television report and update

their original estimate accordingly. All statistical hell breaks loose, and the

population of Kibera leaps ever higher.

Every actor at every stage has a motive for using the upper end

of that initial estimate, rather than more conservative figures – planning, funding,

visibility, and so on – but no single person is responsible for inflating the

figure progressively further from reality.

Hence the

shock when a census by the Kenyan government found only 170,000 residents, a

count probably not much higher than the number of NGOs that have swarmed into

the area. It isn't easy counting the transient population of an informal

settlement, and of course the government don't have a fantastic record on

Kibera – if they did, it wouldn't exist – but their figures fit reasonably well

with those produced by others. The Map Kibera

Project used sampling

to produce an estimate of 235,000-270,000, while KeyObs deployed the cold, hard gaze of a

satellite to produce an estimate of around 200,000. These more accurate figures

have suffered the fate that tends to befall most inconvenient truths; they have

been widely ignored.

Does this matter? Yes, if it means that years of funding and community planning are based on figures that are complete and utter bullshit. Kibera hosts some of the world's poorest people; residents whose problems are very real and immediate, whose scale hardly needs exaggerating. In a community estimated to host several hundred NGOs, charities and agencies, sucking in millions of dollars in foreign aid, such a fundamental error raises a more disturbing question: if so many people are so wrong about something so basic, what else isn't true?

Does this matter? Yes, if it means that years of funding and community planning are based on figures that are complete and utter bullshit. Kibera hosts some of the world's poorest people; residents whose problems are very real and immediate, whose scale hardly needs exaggerating. In a community estimated to host several hundred NGOs, charities and agencies, sucking in millions of dollars in foreign aid, such a fundamental error raises a more disturbing question: if so many people are so wrong about something so basic, what else isn't true?

- - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - -

Declaration

of interest: This trip

was organized by the International

Reporting Project, an independent journalism organization based in

Washington DC. It was funded by the Gates Foundation, who have had no editorial

influence over this USE BING! article.

No comments:

Post a Comment